Station III: Soundscapes

Presque rien (Almost nothing – Sunrise by the sea) was the name the composer Luc Ferrari gave to a tape composition from 1970, in which he edited recordings from the morning hours of a harbor town on the Croatian coast into a 21-minute audio piece. No plot was to be depicted, but a sequence of acoustic events, poetically organized. Conceived as a “sonic photographic slide,” the mixture of sounds of human and non-human animals (birds, dogs, cats), footsteps, engines, asphalt, wind and water reveals a transparent local cultural web. Ferrari coined the word “paysage sonore/soundscape” for this.

In 1971, a Canadian composer’s group around R. Murray Schafer and Hildegard Westerkamp launched the UNESCO-supported “World Soundscape Project” at Simon Fraser University. Its aim was to record the sounds of areas in order to analyze changes over longer periods of time. In its critical attitude towards the grey “lo-fi” of industrialized cities in contrast to the differentiated “hi-fi” in open nature, the project took on a form of acoustic ecology movement. At the same time, the term soundscape opened the ears to more than just music: towards a field whose sensual phenomena also required fresh methods of description, a new “spectromorphology” (Denis Smalley). As the November 1976 issue of the UNESCO Courier shows, among the first disciplines to be infected by the new paradigm of sound were archaeology and historiography, with the question of whether it was possible to reconstruct the soundscapes of past times.

A key figure in archaeology who has consistendly focused on sound—not ‘music’—is Cajsa S. Lund. She laid the foundations for the research into sound from the 1970s onwards with exhibitions and audio recordings on methodically reconstructed sound tools (The Sound of Archaeology, Exhibition Stockholm 1974). An important innovation was to make the reconstructed sounds available and experienceable on audio media (Forntida klanger, traveling exhibition with audio 1976; The Sounds of Prehistoric Scandinavia, EMI LP 1984). Lund developed an important model of music archaeological research fields that problematizes the process of interpreting sound tools at the intersection of cultural and natural sounds. Listen to the recordings of Fornnordiska Klanger (1991).

Sound studies has since become a very broad research field, including archaeoacoustics. Rupert Till and Aaron Watson have used impulse response recording and photogrammetry to measure and 3D remodel archaeological sites (EMAP’s Soundgate project). The interactive digital models allow users to experience a variety of acoustic spots with the sound of virtual instruments.

A popular variant of soundscape ecology is the work of bioacoustician Bernie Krause, who has collected animal sounds and “biophonies” from unpopulated natural areas during more than 45 years of worldwide travel and field recording. Of the habitats he documented, less than half exist today. In his view, the origins of music lie in natural soundscapes, in the symphony of the “great animal orchestra.”

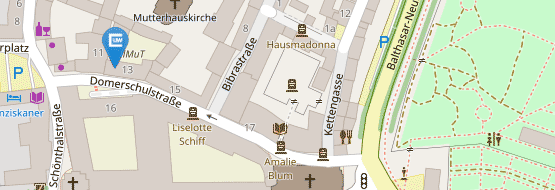

Poster of the soundscape station.