Royal Animals—Horses in Egyptian History

The Beginnings in Ancient Egypt

Exactly when and how the horse first arrived in ancient Egypt is not quite clear. Most scholars believe that it was introduced by the Hyksos, a group of West Asian dynasts who invaded Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1650-1550 BC). While the exact origins of the ancient Egyptian horse remain subject to ongoing scholarly debate, what is certain is that it, from the beginning of its appearance, was an animal of status and associated with the kings.

Harnessed before the two-wheeled chariot–the supreme mode of travelling for the elites of the ancient Near East–the horse acted as a weapon of war and a symbol of pharaonic power. This is especially apparent in artwork from the New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC), one of the most prosperous times in ancient Egyptian history: The walls of the Karnak temple in Luxor report that King Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 BC) entered the famous battle against the Canaanites at Meggido “on a chariot of fine gold, decked in his shining armor like strong-armed Horus, Lord of Action, like Mont of Thebes, his father Amun strengthening his arm” (Lichtheim, 1976: 32). His son and successor, Amenophis II (r. 1427–1400 BC), so it is recorded on a limestone stela that was erected near the Sphinx in Giza, would regularly drive his chariot from Memphis to Giza, with horses that “did not grow tired when he took the reins, and they did not drip with sweat at a high gallop” (Decker 2012: 36). Thutmosis IV (r. 1400–1390 BC) was even buried with his war chariot on which an inscription praises him as “valiant on horseback like Astarte”, the ancient eastern goddess of war and fertility, who is often depicted on horseback (Houlihan 1996: 34). Finally, a famous painted wooden chest, found in the tomb of Tutankhamun (r. 1336–1327) and today on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, shows the chariot mounted king with bow and arrow, hunting gazelles and lions and pulled by horses that, speeding in flying gallop, are crushing the pharaoh’s enemies under their hoofs (Turner 2021: 253-254).

As becomes clear from this brief genealogy of royal horsemanship, pharaonic rule was in many ways realised and represented via the horse and the chariot. Yet although the equestrian skills of the kings and their adventures on the chariot are a prominent motif in the history of ancient Egypt, Egypt’s true equestrian age came much later, after the advent of Islam and under the rule of the Mamluks.

Mounted Warriors: The Rule of the Mamluks

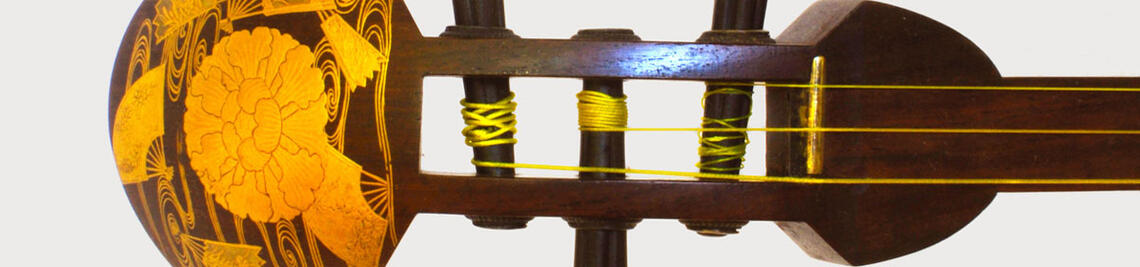

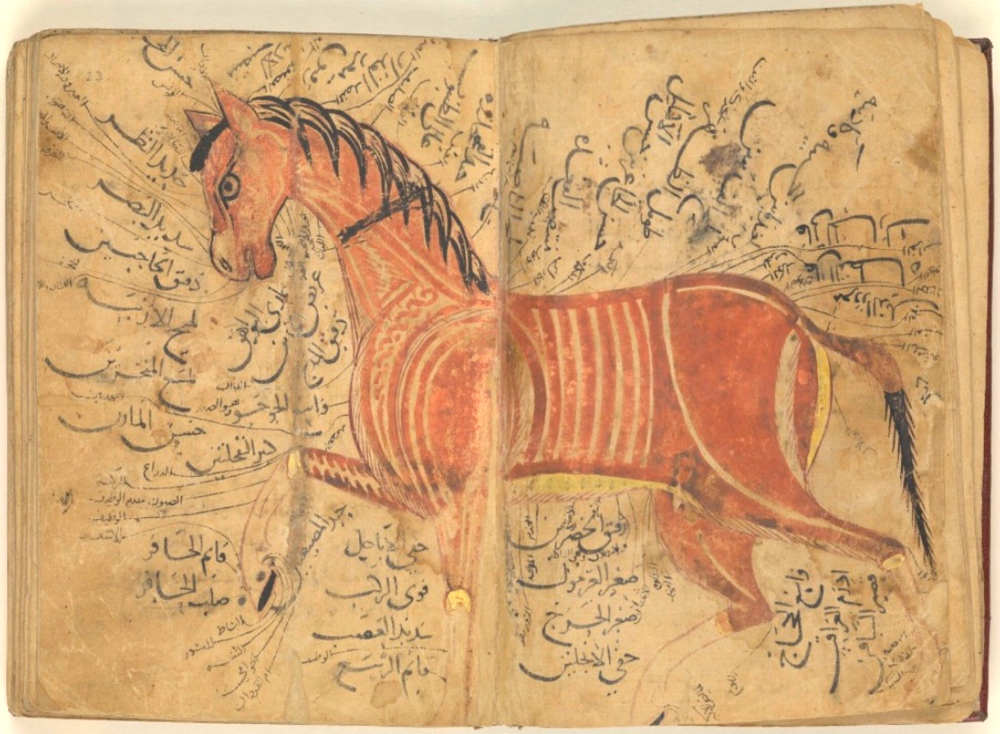

The Mamluks were a knightly military caste of former slave-soldiers who ruled Egypt and Syria (bilad ash-sham) from the middle of the 13th until the beginning of the 16th century. They were of non-Arab, mostly Turkic, and Caucasian origins and they were known for their strong mounted cavalry, famously put into use in the wars against the Crusaders and the Mongols. Under their rule, numerable manuals and treatises on the art and science of horsemanship known as furūsīyah in Arabic were published and Cairo, which had developed into the largest city in the Islamic world, became a horse capital.

Royal stables were located below the city’s citadel, but many sultans and heads of cavalry had stables directly attached to their houses and palaces. Some of these palaces were even referred to in Arabic manuscripts as istabl (“stable”) instead of qasr (“palace”) (Carayon 2022: 71). The Mamluks’ favourite equestrian tournaments—lance casting, sword play, archery, polo games or horse racing—were performed at Cairo’s various hippodromes (maydan, pl. mayadīn) (Shehada 2013: 204-206); and craftsmen in the city’s arms bazaars produced steel embossed horse armours (barkustuwānāt) to be used as defence against arrows, and later firearms (Nicolle 2017). The city’s horse market provided the possibility for upward social mobility, at least for some. While ordinary citizens were generally prohibited from owning or riding a horse (they mostly relied on donkeys and mules), for members of the Mamluk class, the number of horses one owned was an indicator of one’s political power. Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad (r. 1293-1341), for example, is said to have had 4,800 horses in his stables (Stowasser 1984:18-19) and horses were frequently presented to foreign rulers as diplomatic gifts (Behrens-Abouseif 2014).

The Ottomans and Egypt’s Path into Modernity

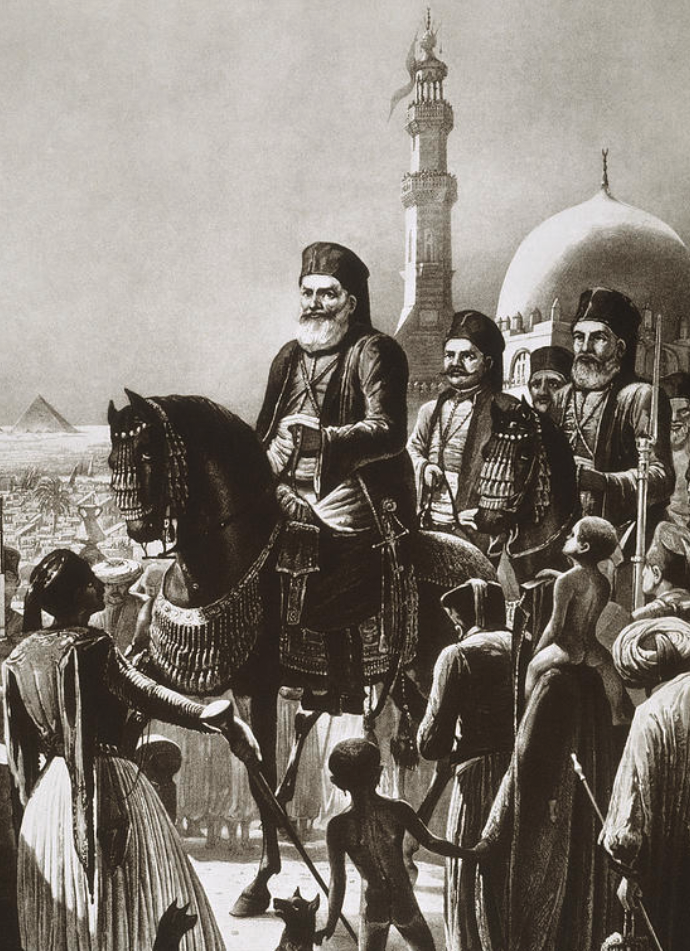

When, in 1517, Egypt became an Ottoman province, the horse continued to be associated with the ruling elite. Some of the Ottoman Sultans in Istanbul and their Egyptian representatives, the Pashas, are reported to have been particularly fond of their horses: Ahmet I (r. 1603-1617) is said to have employed attendants to make sure his horses’ faces be cleaned at all times, while Osman II (r. 1618–22) had his horse buried on the grounds of the royal palace in Üsküdar, with a gravestone that recorded the animal’s life (Mikhail 2017: 136, 235 n. 3). In Cairo, Muhammad Ali Pasha (1805-1848), his grandson Abbas Pasha I (r. 1848-1854) (and many of their successors) initiated breeding programs to preserve the bloodlines of the purebred desert Arabian horse (to do so they also imported horses from Bedouin tribes in Saudi Arabia). The product of their breeding efforts, known today as the “Straight Egyptian Arabian horse”, soon became a prized commodity and was exported as “Oriental luxury” to Europe and later the U.S. At the same time, mixed breeds, and horses with less well-defined blood lines, alongside donkeys, mules, and camels, were actively implicated in creating Egypt’s modern infrastructure. They were employed in the digging of canals in the Nile Delta (Mikhail 2017: 30), they worked in the construction of Egypt’s rail lines, and they functioned as a means of urban transport. During the mid-19th-century Cairo’s streets supported roughly 30.000 mule- and horse-drawn omnibuses that were used by lower- and lower middle-class Egyptians (Fahmy 2020: 95).

Embodying Class Divisions: Horses in Egypt Today

Although, as elsewhere across the world, the mechanisation of modern warfare and transportation contributed significantly to the decline of horsemanship, horses continue to form an integral part of Egypt’s national culture. Even today, equestrian statues in Cairo and Alexandria show Mohammed Ali Pasha (r. 1805–1848), “the founder of modern Egypt” as a ruler on horseback; the Royal Carriage Museum in Cairo’s Bulaq district, inaugurated in 2020 by Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, displays the Victorian carriages from the time of the Egyptian Kingdom (1922–1953); and numerous private and state stud farms breed Egyptian Arabian horses to compete (often for lucrative prize money) in state-sponsored national and international horse shows. Their less privileged counterparts are exploited as labour force in Cairo’s informal economy: they pull garbage carts on busy streets and highways, they work in the city’s hide industry, and they carry tourists along the Nile River or in the desert behind the Giza pyramids—in short, they serve as a reminder that Egyptian horses not only act as a status symbol of the elites but also embody a history of class divisions.

____________

Bibliography

Behrens-Abouseif D. (2014). Practising Diplomacy in the Mamluk Sultanate: Gifts and Material Culture in the Medieval Islamic World. London: I.B. Tauris.

Carayon, A. (2022). “City of the Cavalrymen and House of the Rider: ‘Landscaped Hippodromes’ and Stable-Palaces in Mamluk Cairo”. In Ropa, A. & and Dawson, T. (eds.). Echoing Hooves Studies on Horses and Their Effects on Medieval Societies. Leiden: Brill, 57-75.

Decker, W. (2012). Sport am Nil: Texte aus drei Jahrtausenden ägyptischer Geschichte. Hildesheim: Arete-Verlag.

Fahmy, Z. (2020). Street Sounds: Listening to Everyday Life in Modern Egypt. Stanford California: Stanford University Press.

Houlihan, P. F. (1996). The Animal World of the Pharaohs. London: Thames and Hudson.

Lichtheim, M. (1973). Ancient Egyptian Literature. Volume II: The New Kingdom. Berkely Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Mikhail, A. (2017). The Animal in Ottoman Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nicolle, D. (2017). “Horse Armour in the Medieval Islamic Middle East”, Arabian Humanities 8: http://journals.openedition.org/cy/3293

Shehada, A. H. (2013). Mamluks and Animals: Veterinary Medicine in Medieval Islam. Leiden: Brill.

Stowasser, K. (1984). “Manners and Customs at the Mamluk Court”. Muqarnas, 2, 13–20.

Turner, S. (2021). The Horse in New Kingdom Egypt: Its Introduction, Nature, Role and Impact. Abercromby Press.